Why El Paso has a pediatric endocrinologist shortage

This story is the second in a two-part series about Dr. Hector Granados, the shortage of pediatric endocrinologists and how this lack of specialized health care impacts El Paso families. Click here to read Part 1.

El Paso mother Jennifer Oguete calls her daughter her miracle baby.

Oguete’s daughter, Jaelynn, was born in El Paso at 29 weeks. The baby weighed 2 pounds and made a whimper of a cry before the delivery team rushed her to the NICU. Jaelynn was bald, brown eyed and “just a teeny tiny thing,” Oguete described.

A year later, Jaelynn’s general pediatrician diagnosed her with failure to thrive, a condition that describes infants and children who aren’t growing at a normal rate. The doctor referred her to Dr. Hector Granados, a pediatric endocrinologist she still sees today.

Jaelynn, who just turned 9, has gotten used to her visits with Granados – first for delayed growth, then hypothyroidism and now Type 1 diabetes. He is one of only two pediatric endocrinologists in El Paso. The other, Dr. Sanjeet Sandhu, works at Granados’ private practice where they receive an estimated average of 200 new patient referrals a month, Granados said.

But a pending lawsuit from the office of Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton now threatens Granados’ medical license and could force families to find another health care provider.

Paxton sued Granados on Oct. 29 for allegedly providing gender-affirming treatment to minors. Granados is one of three Texas doctors Paxton accused last year of violating SB 14, a state law that prohibits health care workers from providing puberty blockers or hormones to minors for transitioning genders.

Granados denied the allegations. His attorney, Mark Bracken, filed a motion Nov. 25 to transfer the case from Kaufman County, where it was filed, to El Paso County, where Granados practices.

Bracken, who has Type 1 diabetes, grew up in El Paso. He said his personal experience makes him aware of how the outcome of this case could affect a geographically isolated community that struggles to recruit and retain specialty doctors. His 9-year-old daughter also has Type 1 diabetes and has been a patient of Granados since she was 3.

“El Paso’s a difficult place to recruit professionals and physicians who aren’t from our community and are unfamiliar with it,” Bracken said. “Dr. Granados is from the borderland. Typically, if someone has a connection to our city, that’s our best chance to convince them to move here. Until people visit and get to know El Paso, they just know what they see on TV or social media.”

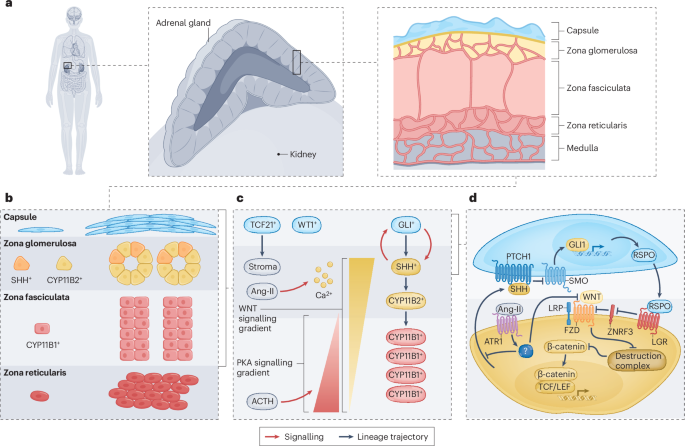

Pediatric endocrinologists treat a variety of conditions including diabetes, thyroid disorders, pituitary gland disorders, growth deficiencies, precocious puberty and differences of sexual development.

Outside of El Paso, the next closest pediatric endocrinologists are in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Tucson, Arizona, none of which accept CHIP or Medicaid from patients in Texas.

To stay in Texas, El Paso families can go to Lubbock or travel even greater distances to get on the waitlist in a bigger city.

Oguete said she already travels out of town to take Jaelynn to doctor appointments – a rheumatologist in Phoenix and a gastrointestinal motility specialist in Fort Worth every six months, in addition to numerous specialists and a general pediatrician in El Paso.

“Our months are filled with doctor appointments,” Oguete said. “You think you’re OK because you got out of NICU, because she grew and she’s perfect. Things just start showing up as they get older.”

It didn’t take much to convince Granados to return to El Paso in 2014. He calls the binational region of El Paso-Juárez home.

After receiving his medical degree from Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, he completed his residency in general pediatrics at Woodhull Medical Center, affiliated with New York University, and fellowship in pediatric endocrinology at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, affiliated with the University of Connecticut. Granados said a diabetes club in Juárez, where he helped families live healthier lifestyles to manage their diabetes, sparked his interest in endocrinology.

In 2014, he joined Texas Tech Health El Paso as part of a group of four pediatric endocrinologists. After the departure of Dr. Krishnaswamy Rao, only Granados remains in El Paso from that group.

Rao left in late 2021 and began practicing in Temple, Texas, located between Waco and Austin.

Both she and Granados treated transgender youths while they were at Texas Tech Health El Paso, which opened the city’s first Children & Adolescent Gender Clinic in 2015. The clinic has since closed.

What are puberty blockers and hormone replacement therapy used for?

Gender dysphoria describes the distress caused when a person’s gender identity doesn’t match the sex assigned at birth. Studies show adolescents with gender dysphoria have high rates of mental health disorders and suicidal behavior.

Before SB 14, pediatricians could help patients transition to the gender they identify with by putting them on a carefully monitored treatment plan involving puberty blockers or hormone replacement therapy, or HRT.

Pediatric endocrinologists also prescribe puberty blockers and HRT for other reasons.

Paxton’s lawsuit accuses Granados of prescribing puberty blockers to transgender patients under the false diagnosis of precocious puberty, a condition where children experience puberty too early.

Vanessa Keyser-Casas remembers when she and her daughter, Victoria, received a referral to see Dr. Sandhu in El Paso after years of insisting that something didn’t seem right. Victoria, then 16, had yet to menstruate. She had also stopped growing at 4 feet, 9 inches, never hitting the growth spurt her peers experienced.

Bloodwork and an ultrasound confirmed a diagnosis: Turner syndrome, a genetic condition affecting females where one of the X chromosomes is missing or partially missing. Victoria said it felt “a little heartbreaking” when she saw the ultrasound results, which revealed her ovaries were almost nonexistent and nonfunctioning, rendering her infertile.

But mostly she just felt relieved to know why her body was different from the other girls.

Sandhu started her on the estrogen patch and later added a prescription for progesterone pills. After starting estrogen, Victoria, who’s 18 now, experienced her first period and has a cycle, albeit an irregular one. She also recognizes the other benefits of HRT, from female body development to bone health to mood regulation.

“All the medication really just changed my life,” Victoria said. “It put me on track to be semi-normal. You add a couple things to your body and it can completely change not only how you see yourself, but how you see the world.”

Why are there so few pediatric endocrinologists in El Paso?

Keyser-Casas said it should not have taken so long for her daughter to be referred to a specialist. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends starting estrogen replacement in the preteen years.

“We wouldn’t have been ignored for so long if we had more specialties, more access, more knowledge,” Keyser-Casas said. “People leave and go and nobody comes back to work here, leaving this huge lack of knowledge in this city.”

More than 220,000 people living in El Paso County are younger than 18. Compared to similarly sized cities, Albuquerque has four board-certified pediatric endocrinologists and Tucson has six, according to the American Board of Pediatrics.

Granados’ practice serves a vast stretch of West Texas to Southern New Mexico, with patients traveling from as far as Silver City, New Mexico, and Van Horn, Texas, he said. El Paso’s relative isolation from other large cities means the city has to cover a wide area of underserved populations, he said.

Along with emergency room visits, he also checks on preterm babies in NICU who have hormonal imbalances.

Nationwide, the country is experiencing a shortage of pediatric endocrinologists.

Data from the American Board of Pediatrics shows that of the 100 positions offered last year in pediatric endocrinology residencies and fellowships, 40 went unfilled.

Demanding workloads, an aging workforce, trainees’ limited exposure to the subspeciality and increasing medical student debt may have contributed to the decline in pediatric endocrinologists, according to a report published last year in the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

While pediatric endocrinologists undergo three additional years of training after their residency, they get paid less on average than general pediatricians and other pediatric subspecialists.

Dr. Michele Zerah, a longtime pediatric endocrinologist, said she made the difficult decision to resign and retire last year to take care of family health issues.

While working part-time at Texas Tech Health El Paso, she saw about 20 to 25 patients a week, plus additional patients she saw at the hospitals, for various conditions, from hypoglycemia to atypical genitalia. She also introduced medical residents and students to her subspeciality, teaching them how to examine patients for endocrine conditions. She hoped to spark someone’s interest in the field.

“It takes a lot,” Zerah said. “A good pediatric endocrinologist’s job is never done. You get home and still worry about the patient.”

Zerah worked in Albuquerque before moving to El Paso in 2017 to help start the pediatric endocrinology clinic at Providence Children’s Hospital. She then joined Texas Tech Health El Paso at the end of 2022 where she also worked as an assistant professor, but departed at the end of August last year.

Before resigning, Zerah said the university and El Paso Children’s Hospital had been trying to recruit pediatric endocrinologists. Zerah said she gave them two pieces of advice: Pay more and hire at least two at the same time.

Having more pediatric endocrinologists in town means they can share the workload and emergency calls, she said.

Texas Tech Health El Paso did not respond to El Paso Matters’ request for comment.

“It’s a generational thing,” Zerah said. “Young people want to stay where there’s a big group so they can have a normal lifestyle, work-life balance. Burnout is a big deal in medicine.”

Diabetes, endocrine concerns prevalent among El Paso youths

In addition to overnight calls for diabetes emergencies, pediatric endocrinologists are treating an expanding spectrum of conditions, including patients whose endocrine systems were affected by cancer treatments and organ transplant patients, according to the 2024 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Ilena Alvarez knows what it’s like to see a rotation of doctors and nurse practitioners. Her 8-year-old son Ferran has Down syndrome and sees different therapists each week. He also sees a pediatric psychiatrist for ADHD, and every six months a nurse practitioner at Granados’ office in Far East El Paso.

Ferran was about three when he was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, a condition when the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormones, which can delay a child’s growth.

Since starting his medication, Ferran began growing faster, growing more hair and having more energy, Alvarez said. She feels lucky that her son is relatively healthy, and has a less severe endocrine condition that’s simple to manage, just a pill every day.

The Texas AG lawsuit makes her unhappy, though.

“I’m gonna be honest, I’m kinda pissed,” Alvarez said. “It’s very annoying because, one, we don’t have doctors here and, two, I think medical decisions should be between the doctor and patients, in this case parents. I think it’s a waste of time and resources and if they remove his license, it’s going to be a big impact on the community.”

“My son’s case is not so serious, but for other people, it could be a matter of life or death,” she continued. “We also have to consider not just our city, but the region.”

It’s common for residents in Juárez and El Paso to travel back and forth for health care. If Granados had to shut down his practice and there were no other options in town, Alvarez said she would try to find a new pediatric endocrinologist in Juárez or farther in Ciudad de Chihuahua, where she used to live.

Ferran is enrolled in Texas Medicaid and Alvarez thinks it would be more affordable to pay out of pocket in Mexico than in New Mexico.

Type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease, is one of the most common chronic conditions pediatric endocrinologists treat in children. Left untreated it can lead to serious and even fatal complications. Granados says he often diagnoses children with Type 1 diabetes for the first time in the hospital emergency department.

Texas does not have data on the number of youths who have diabetes because it does not require providers to report cases of endocrine disorders, said Chris Van Deusen, a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Health and Human Services. Surveys provide data on adults, but not the pediatric population, he said.

Every year, El Paso Children’s Hospital sees an average of 40 to 50 children with new onset Type 1 diabetes, some admitted via the emergency department and others admitted directly from their pediatrician, said Daniel Veale, a spokesperson for El Paso Children’s Hospital.

The hospital also receives patients with known Type 1 diabetes who are admitted for issues including diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening complication in which the body cannot produce enough insulin and acids build up in the blood and urine.

Granados began seeing Oguete’s daughter Jaelynn after she was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes last year, a few months after her first bout of COVID-19. Jaelynn had already seen Granados to treat growth hormone deficiency, then Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune disorder that causes the body’s immune system to attack her thyroid gland.

This time Oguete noticed her daughter was drinking more water and peeing more often. By the time Jaelynn made it to a hospital emergency room, her blood sugar began dropping.

“My poor child,” Oguete said. “She wasn’t really happy, wasn’t happy at all. She asked, ‘Why do things always have to happen to me?’ As a parent, that’s really hard to explain.”

After the coronavirus pandemic began in 2020, Granados and Zerah said they saw an increase in diabetic children, which has created a greater demand for epidemiology services in El Paso.

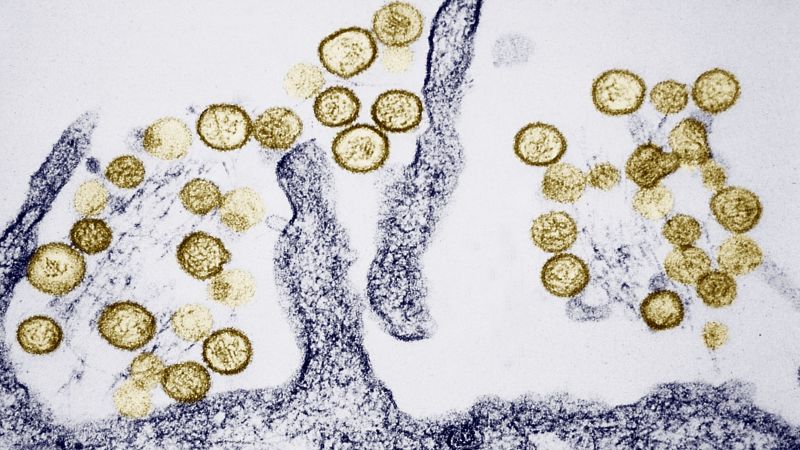

Numerous studies have tried to determine whether there’s a link between COVID-19 and diabetes. One 2021 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found people younger than 18 with COVID-19 were more likely to be newly diagnosed with diabetes, Type 1 or Type 2, in the months after infection than those without COVID-19.

The study does not establish that COVID-19 can cause diabetes and more studies are needed to fully understand this connection, said CDC epidemiologist Alain Koyama. One possible association is the effects of COVID-19 infections on organ systems involved in diabetes risk, Koyama said.

Potential consequences of Texas AG lawsuit

Doctors who violate SB 14 risk losing their medical license

Paxton has sued two other pediatricians in Texas for allegedly providing gender-affirming care to minors: Dr. Mary Lau and Dr. M. Brett Cooper at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Oguete said if El Paso loses Granados’ practice, she would rather travel to New Mexico or Arizona than to another pediatric endocrinologist in Texas. It’s not worth the risk of Paxton targeting another doctor in Texas and having to change providers again, Oguete said.

This is already the reality for transgender youth in El Paso, who must either wait until they turn 18 to access gender-affirming care or travel out of state before that.

Families in El Paso told El Paso Matters this lawsuit could make it harder to recruit pediatric endocrinologists to Texas – similar to how the Texas abortion ban has strained the OB-GYN workforce.

Texas is seeing the closure of programs providing critical health care to adolescents and longtime providers leaving the state, said Karen Loewy, senior counsel and director of constitutional law practice at Lambda Legal.

Lambda Legal was one of the organizations that challenged SB 14, but the Texas Supreme Court upheld the law.

Pediatricians are leaving because they want to provide patients with the full range of medically necessary care – without Paxton interfering with their relationships with patients and families, Loewy said.

“Not only will transgender young people continue to suffer, but all kids who need the kinds of care these doctors provide,” Loewy said.

link